The final piece of ethics advice that I want to look at is from the last of the three big ethical theories in philosophy. Last week I talked about deontology, and the week before about consequentialism, but this week is all about the advice we can get from virtue ethics and how it compares to the golden rule.

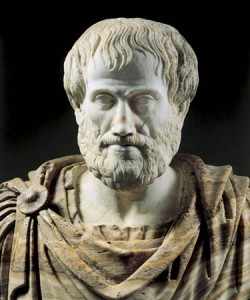

Virtue ethics is a school of thought pioneered by Aristotle about 2400 years ago, and it’s undergone a lot of thought in the past few thousand years. Instead of laying out rules and guidelines for people to follow, it focuses on picking out a virtue, which is the middle point between two vices. For example, being courageous is virtuous, but if you have too much courage, it makes you reckless. If you have too little, then you’re a coward. A lot of the virtues are pretty intuitive, though some, like wit, are a little odd. I’d certainly prefer it if we were all wittier, but I’m not sure that we have an ethical obligation to be that way. A lot of the strangeness comes from how Aristotle thought about people, and expressing the virtues isn’t so much about looking out for others as it is about being the best human you can. But how do you do that? He has a bit of advice, which I’ll paraphrase.

Virtue ethics is a school of thought pioneered by Aristotle about 2400 years ago, and it’s undergone a lot of thought in the past few thousand years. Instead of laying out rules and guidelines for people to follow, it focuses on picking out a virtue, which is the middle point between two vices. For example, being courageous is virtuous, but if you have too much courage, it makes you reckless. If you have too little, then you’re a coward. A lot of the virtues are pretty intuitive, though some, like wit, are a little odd. I’d certainly prefer it if we were all wittier, but I’m not sure that we have an ethical obligation to be that way. A lot of the strangeness comes from how Aristotle thought about people, and expressing the virtues isn’t so much about looking out for others as it is about being the best human you can. But how do you do that? He has a bit of advice, which I’ll paraphrase.

“Find someone who’s already virtuous, and do what they would do.”

That’s it. Think of a person who has the virtues, and when you find yourself in a difficult situation, do what they would do. Popular candidates for paragons of virtue include Jesus, Mahatma Gandhi, Socrates, and my personal favourite, Superman. You see, for Aristotle, when you have an ethical difficulty, you’re not wondering what you should do. Well, you might be, but that’s the wrong way to think about it. You want to think about the kind of person you want to be. That’s where the virtues come in. So finding a paragon of virtue means finding someone that you want to be like, and emulating them. It’s about cultivating a habit of acting well, and learning from example.

That’s it. Think of a person who has the virtues, and when you find yourself in a difficult situation, do what they would do. Popular candidates for paragons of virtue include Jesus, Mahatma Gandhi, Socrates, and my personal favourite, Superman. You see, for Aristotle, when you have an ethical difficulty, you’re not wondering what you should do. Well, you might be, but that’s the wrong way to think about it. You want to think about the kind of person you want to be. That’s where the virtues come in. So finding a paragon of virtue means finding someone that you want to be like, and emulating them. It’s about cultivating a habit of acting well, and learning from example.

Now, there are some difficulties with this, the first one being that some of these paragons aren’t really equipped to deal with modern problems. Socrates doesn’t have a lot to say about cloning or filesharing, and imagining what he’d do is an exercise in futility. You’d have to invent so much about Socrates or extrapolate so wildly from his writings that you’d be better off making up your mind some other way. Another issue is how we recognize paragons of virtue, which goes along with the problem of deviant values for the golden rule. What if, instead of picking Superman as my paragon, I picked Genghis Khan? He’s the most successful human being in the history of the world, and maybe that’s what I value. What would Genghis Khan do? He’d chop off your head and ride off with your wife pretty much every time. I’m oversimplifying this a bit, because someone we’d hold up as a paragon of virtue should arguably have all of the virtues, and Genghis Khan isn’t quite there on wit or appropriate ambition. But it’s hard to find a person, real or fictional, who genuinely has all the virtues. Jesus had a wicked temper, and it’s hard to say whether or not Superman is really being courageous.

In terms of advice though, it’s directive, followable, and action-guiding. Oddly enough, the real question is whether it’s ethical. Kant, the philosopher I talked about last week, raised an interesting point. It seems possible to be courageous, witty, appropriately ambitious, et cetera, and still be a villain. In fact, you’d be highly proficient at villainy. Stacked up against the golden rule, I’d have to call this a tie. the theory is, as with all the others, far more developed, but as a quick piece of advice, it’s okay but not great.

And that’s all for today. Next week I’ll do an advice roundup, and this Saturday you can look forward to our first logical fallacy (okay, probably not the first one on the site, but the first one I’m looking at in depth. Shush).

I tend to look up to paragons of virtue among friendly strangers who turned into the strangest friends of mine. They often have something unique to discover deep inside their souls, to appreciate, exaggerate and idolize. Then their precious spirits can embody my morals whenever I feel stuck in myself during life challenges. There is only one disadvantage to such kind of shamanic empathy. An unstable personality can frighten people who expect me to obey stereotypes.