One of the biggest considerations in ethics is the idea that having different ethical obligations to different people requires there to be some morally relevant difference between them. Humans have counted all kinds of things as morally relevant, in the past and even today, but some of those things aren’t. The toddler test is a simple way to figure out whether something is a morally relevant difference in a lot of cases (no actual toddlers were harmed in the production of this post).

But first, what is moral relevance, really? To understand moral relevance, I like to start with practical relevance. If you’re camping, and want to make a fire, you can sort objects by their practical relevance. Things like lighters and kindling are very relevant to your goal, as are flint and steel if you’re an Eagle Scout. Other objects you have around your camp site are not relevant to the task, like marshmallows and tents. Some objects are in between, like clothes and picnic tables. They could help you start a fire, but you have other important uses for them. The relevant differences between these objects is their ability to help you make a fire, and that’s what you take into account when choosing your tools. Because of these relevant differences, you accord each item a different significance. For example, you don’t rule out marshmallows when starting a fire. You don’t have to, because you understand that marshmallows deserve no consideration when starting a camp fire. They’re not going to help.

Moral relevance works in a similar way. Humans are highly elaborate people sorters, and there are a lot of differences to choose from. Moral significance involves our obligations to a person. If someone is given more or less moral significance, then we have more or less obligations to them, and this different significance exists in virtue of the differences between us. But it’s not quite that simple. Some differences are morally relevant, and some aren’t. The really hard part is figuring out which ones are relevant. Here are some examples:

Skin Colour

People certainly used to think that this was a morally relevant difference, and while it’s true that less people think that now, less isn’t none. For hundreds of years after the colonization of Africa and the Americas, skin colour could be the difference between being considered a person and being considered property. Even after the abolition of slavery, it was seen as a reason to segregate people and treat them differently. In Canada, my country which prides itself on multiculturalism and general politeness, the last segregated school closed in 1983. But colour isn’t a morally relevant difference, and that seems easy to show with an example I’m going to use a lot. Let’s imagine that there’s a burning nursery, and you know that there are two toddlers inside at opposite ends. It takes an equal amount of effort to get to them, but you only have time to save one. One of them is white, and the other one is black. The question then is “Should the colour of their skin be relevant in deciding which one to save?” It’s a yes or no question, but one whose answer requires some justification. Those are the justifications which are going to be important to seeing whether it’s morally relevant, because they’re the reasons you think it is.

People certainly used to think that this was a morally relevant difference, and while it’s true that less people think that now, less isn’t none. For hundreds of years after the colonization of Africa and the Americas, skin colour could be the difference between being considered a person and being considered property. Even after the abolition of slavery, it was seen as a reason to segregate people and treat them differently. In Canada, my country which prides itself on multiculturalism and general politeness, the last segregated school closed in 1983. But colour isn’t a morally relevant difference, and that seems easy to show with an example I’m going to use a lot. Let’s imagine that there’s a burning nursery, and you know that there are two toddlers inside at opposite ends. It takes an equal amount of effort to get to them, but you only have time to save one. One of them is white, and the other one is black. The question then is “Should the colour of their skin be relevant in deciding which one to save?” It’s a yes or no question, but one whose answer requires some justification. Those are the justifications which are going to be important to seeing whether it’s morally relevant, because they’re the reasons you think it is.

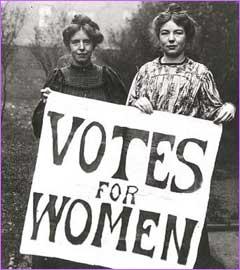

Gender

Gender has been considered a relevant difference even longer than skin colour, and  women were considered property for a very long time, even in nations who claimed to have abolished slavery. Wedding vows and ceremonies reflect this, where the bride is given away by her father into the possession of her husband. This is also apparent in the history of suffrage, when women fought for the right to vote and hold offices, that is to be given all of the rights of citizenship. In Canada, women couldn’t vote until 1918, and even that was just caucasian women. First Nations people, including women, didn’t get the vote until 1960. Is gender a morally relevant difference? Let’s ask our toddlers. If the only difference between the two toddlers is their gender, is that a good reason to save one over the other?

women were considered property for a very long time, even in nations who claimed to have abolished slavery. Wedding vows and ceremonies reflect this, where the bride is given away by her father into the possession of her husband. This is also apparent in the history of suffrage, when women fought for the right to vote and hold offices, that is to be given all of the rights of citizenship. In Canada, women couldn’t vote until 1918, and even that was just caucasian women. First Nations people, including women, didn’t get the vote until 1960. Is gender a morally relevant difference? Let’s ask our toddlers. If the only difference between the two toddlers is their gender, is that a good reason to save one over the other?

The toddler example can be repeated for all kinds of cases, such as sexual orientation, nationality, socio-economic status, family tree, and disability. Since it applies in all of these cases, you might be thinking that maybe there are just no morally relevant differences. Everyone is equal, and due the exact same amount of consideration as everybody else. That seems fair, after all. But there are differences which are relevant, and the toddler example shows one of them. The relevant difference between the toddlers and everyone else is vulnerability. The toddlers are in harm’s way in a way which bystanders are not. The fact that you can only save one doesn’t affect the fact that you ought to save at least one, and that obligation comes from their vulnerability.

Being vulnerable means that some of our well-being is not in our control. It’s up to chance, other people, or to structures that people have created. Both the civil rights and the suffrage movements were bids by portions of society who systematically had their well-being taken out of their hands, quite literally. When we deny someone a vote, we deny their ability to help decide what’s best for their country, and ultimately for them. Same with denying them equal rights. They become vulnerable by virtue of differences that you’ve already seen are morally irrelevant. Being vulnerable isn’t always bad, it’s necessary for intimacy, but with intimacy we decide when and how we’re vulnerable. No one else is making us so.

Now, not all morally relevant differences are as cut and dried as this. For example, how we designate personhood gets really thorny, because the line is pretty blurry at points. Not just with fetuses (where it’s actually irrelevant), but also with nonhuman animals. The toddler test serves as a quick and easy way of sorting out a lot of them, though. These kinds of issues come up all the time as we try to sort out our obligations to people and theirs to each other. What are some other differences that seem morally relevant?

Sorry Jim, I’m not sure how much heavy lifting the toddler test is doing. It seems to me that if a person says, “Yeah, definitely save the white kid,” we would NOT take this as evidence that race is a morally relevant feature.

So what you seem to be saying is: “Race isn’t a morally relevant feature; therefore, it shouldn’t be a factor in deciding to save one child over another.” It’s really begging the question.

BUT I, of course, agree that things like race and gender aren’t morally relevant in many contexts; although, in other contexts they’re entirely relevant. I just think that there’s some pre-theoretic/theoretic principles in the background of your post that aren’t actually elucidated by the use of the test.

As Jim knows, I’m an artists, not a philosopher. I was actually giving this topic, specifically the Toddler Test, some thought today, and came back to make a comment. However, after reading philosochick’s comment, I’m actually more confused than when I started, and I’m going to attribute this to my lack of knowledge in the field.

Philosochick, could you explain your first paragraph, and how the questions makes it NOT relevant? Could you also elaborate on what question is being begged?

Cheers

I think you’re right, Philosochick, I was unclear about what exactly I think the Toddler Test does. What it doesn’t do is pick out whether a feature is morally relevant, but what it does do, and what I meant to say, is that it helps get directly to a few things about a person’s beliefs about moral relevance.

For example, if someone says “Yes, I would save the baby because it’s white,” it shows that they hold skin colour to be a morally relevant distinction, and prompts you to ask them why, giving you a justification you can examine, without any hemming or hawing, because they’ve already agreed that it’s the morally salient feature. What could I do to improve this?

Rob,

Begging the question is a technical term for a circular argument which, in claiming that the Toddler Test helps sort out what’s morally relevant, is what I could be making. I’d be saying “Skin colour isn’t morally relevant, and here’s a test that shows this, but getting the right result requires you to already believe that skin colour isn’t relevant.”

Hmmm. Hmmmmmmm. Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm. I thought Jim was Irish? Interesting. Maybe it’s still just that camrea? Or maybe he is re-inventing himself. In that case, more power to him! Re-inventing yourself is lots of fun. You should do that at least once every 5 years, even though your loved-ones might get a bit of stressed out by it. So, All Hail to You, Ghostriding Jim! Curious to meet your new self in two weeks in CO!